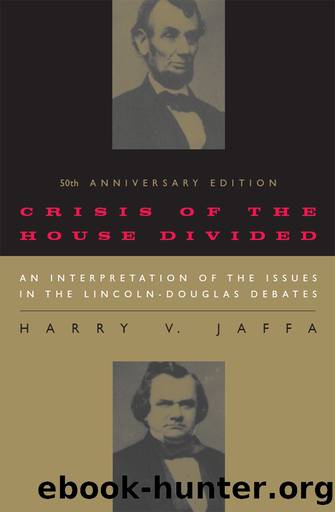

Crisis of the House Divided: An Interpretation of the Issues in the Lincoln-Douglas Debates by Harry V. Jaffa

Author:Harry V. Jaffa [Jaffa, Harry V.]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: The University of Chicago Press

Published: 1959-11-15T00:00:00+00:00

We cannot help noticing that here, unlike the Gettysburg Address, Lincoln calls only for dedication to the legal order, not, as we might have expected, to the Declaration and the Constitution and laws. Yet in this difference we are reminded of the problem from which the Lyceum speech starts: the problem of disorder arising from base passions, passions set in motion by the Revolution and hence by the summons to independence. In fact, the difference between the Lyceum speech and the Gettysburg Address is more apparent than real. For the latter effects a subtle but profound change in the doctrine which it adapts (rather than adopts) from the Declaration of Independence. Throughout the period of the debates with Douglas, the âprophetic periodâ of his career, whose keynote was a return to ancestral ways, Lincoln constantly referred to the great central tenet as an âancient faith.â And so, in the Gettysburg Address, what was called a self-evident truth by Jefferson becomes in Lincolnâs rhetoric an inheritance from âour fathers.â This is not to suggest that Lincoln doubted the evidence for the propositionâalthough we have seen that his assent was far more complicated than that of âthe peopleâ could well beâbut that he found its political efficacy, âfour score and seven yearsâ after, to reside more in the fact of its inheritance than in its accessibility to unassisted human reason. Lincoln transforms a truth open to each man as man into something he shares in virtue of his partnership in the nation. The truth which, in the Declaration, gave each man, as an individual, the right to judge the extent of his obligations to any community in the Gettysburg Address also imposes an overriding obligation to maintain the integrity, moral and physical, of that community which is the bearer of the truth. The sacrifices both engendered and required by that truthâfor the lapses from the faith are, in a sense, due to the moral strain imposed by its loftinessâtransforms that nation dedicated to it from a merely rational and secular one, calculated to âsecure these rightsââi.e., the rights of individualsâinto something whose value is beyond all calculation. The âpeopleâ is no longer conceived in the Gettysburg Address, as it is in the Declaration of Independence, as a contractual union of individuals existing in a present; it is as well a union with ancestors and with posterity; it is organic and sacramental. For the central metaphor of the Gettysburg Address is that of birth and rebirth. And to be bom again, to Lincoln and his audienceâas to any audience reared in the tradition of a civilization shaped by the Bible and by Platoâs Republicâconnoted the birth of the spirit as distinct from the flesh; it meant the birth resulting from the baptism or conversion of the soul. This new birth is not, as we have said, mere renewal of life but the origin of a higher life. Thus Lincoln, in the Civil War, above all in the Gettysburg Address and Second Inaugural, interpreted the war as a kind of blood price for the baptism of the soul of a people.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

The Dawn of Everything by David Graeber & David Wengrow(1707)

The Bomber Mafia by Malcolm Gladwell(1622)

Facing the Mountain by Daniel James Brown(1553)

Submerged Prehistory by Benjamin Jonathan; & Clive Bonsall & Catriona Pickard & Anders Fischer(1455)

Wandering in Strange Lands by Morgan Jerkins(1430)

Tip Top by Bill James(1416)

Driving While Brown: Sheriff Joe Arpaio Versus the Latino Resistance by Terry Greene Sterling & Jude Joffe-Block(1376)

Red Roulette : An Insider's Story of Wealth, Power, Corruption, and Vengeance in Today's China (9781982156176) by Shum Desmond(1359)

Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking of America: A Recent History by Kurt Andersen(1353)

The Way of Fire and Ice: The Living Tradition of Norse Paganism by Ryan Smith(1336)

American Kompromat by Craig Unger(1315)

F*cking History by The Captain(1304)

It Was All a Lie by Stuart Stevens;(1300)

American Dreams by Unknown(1286)

Treasure Islands: Tax Havens and the Men who Stole the World by Nicholas Shaxson(1273)

Evil Geniuses by Kurt Andersen(1257)

White House Inc. by Dan Alexander(1212)

The First Conspiracy by Brad Meltzer & Josh Mensch(1174)

The Fifteen Biggest Lies about the Economy: And Everything Else the Right Doesn't Want You to Know about Taxes, Jobs, and Corporate America by Joshua Holland(1126)